Price/Earnings Ratio

Overview

The P/E ratio is a classic measure of a stock's value, indicating how many years of profits (at the current earnings rate) it would take to recoup an investment in the stock. The current S&P 500 10-year P/E Ratio is 30.9. This is 52.9% above the modern-era market average of 20.2, placing the current P/E ratio 1.3 standard deviations above the modern-era average. This suggests that the market is Overvalued.

Why Does it Matter?

P/E ratios have their limits. To justify a P/E ratio that remains consistently above its historical average for extended periods, the US stock market would not only need to continue growing, but it would have to do so at an increasingly rapid pace.

The chart below illustrates the historical trend of this ratio, as well as its most current value. For further details on the methodology behind this model and our analysis, continue reading below.

Theory

What is a Price-to-Earnings Ratio?

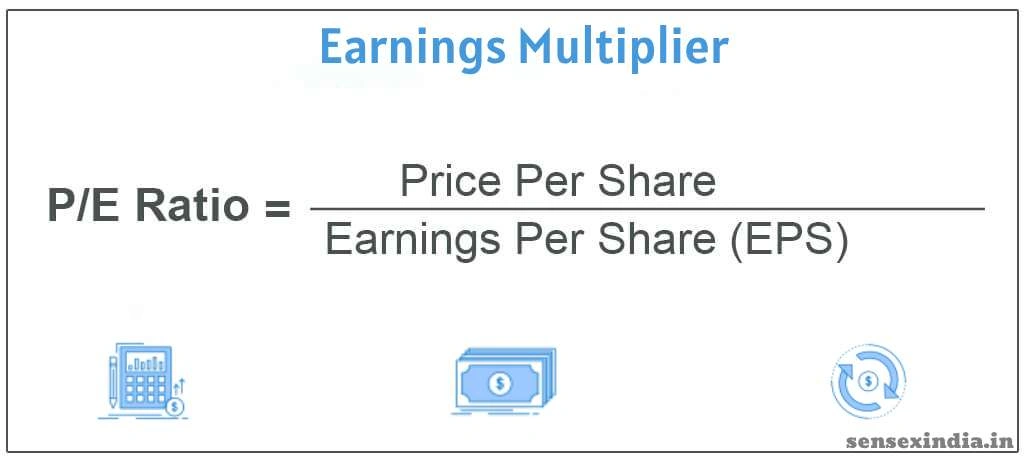

P/E ratios are essential in stock valuation analysis and are commonly used to evaluate individual companies. As the name suggests, the P/E ratio is calculated by dividing a stock's price by the company's annual earnings per share. The underlying concept is that a mature company distributes its profits to shareholders through dividends. Therefore, the P/E ratio indicates how many years it would take for an investor to recover their initial investment. For example, if you buy one share of ACME Co for $100, and ACME consistently earns $10 per share annually, it would take the investor 10 years to recoup their $100 investment.

P/E is based on the most recent actual earnings reported by the company. Let’s consider another example, where we anticipate future earnings growth. Suppose TechCo was founded 5 years ago, and their earnings per share each year were $0, $1, $1.50, $2, and $5. Let’s also assume TechCo’s current share price is $100, similar to ACME in the previous example. Since TechCo's most recent earnings per share is $5, their P/E ratio would be $100 divided by $5, which equals 20. This means that, based on current earnings, investors in TechCo can expect to recover their investment in 20 years. This is double the time it takes for ACME—so why is that? The key difference is TechCo’s profit growth rate. As a newer company, TechCo has been growing its profits rapidly over the last 5 years, leading investors to expect this growth to continue. This is why high-growth companies often have higher P/E ratios—the market anticipates strong future performance compared to current earnings.

The same analysis can be applied to the entire stock market. By adding up the total price of all shares in the S&P 500 and comparing it to the total earnings per share produced by those companies, you can easily calculate the P/E ratio for the US stock market.

Below, you’ll find both the total S&P 500 aggregate value and the aggregate earnings.

Here’s the same chart again, but with a logarithmic axis to better illustrate how the data tracks each other consistently.

Data

The charts above show a clear relationship between price and earnings, especially noticeable in the log chart. A quick glance reveals that both series have generally increased over time, with the S&P 500 price consistently being about 10 to 20 times greater than the annual earnings. By calculating the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio, we can clearly visualize this relationship, as shown below.

P/E10 (CAPE)

The chart above displays the standard calculation of the S&P 500 P/E ratio since 1950. This ratio, which compares the current price with the most recent earnings, can be quite volatile due to business cycle fluctuations. For example, during the depths of the financial crisis in mid-2008, S&P 500 earnings fell by around 90% within a year. While stock prices also dropped significantly, this caused the market’s P/E ratio to soar to over 120 during that time.

For long-term analysis, it's often more useful to use the Cyclically Adjusted Price Earnings (CAPE) ratio instead of the current P/E. The CAPE ratio, which is similar to the traditional P/E, divides the current price by the average earnings over the past 10 years, rather than just using the most recent earnings data. The CAPE ratio, shown below, generally follows the same trend as the current P/E ratio, but it smooths out much of the volatility.

Current Values & Analysis

Creating a Model

The chart below displays the same CAPE ratio data series as the previous chart, but with the y-axis adjusted to a baseline of 0 at the average CAPE ratio value of 20.2. It now features horizontal bands that represent standard deviations from that average. This format aligns with our other valuation models.

Current Position

As of November 30, 2023, the S&P500 P/E ratio is 52.9% (or 1.3 standard deviations) above its modern era average. By this valuation, the market is Overvalued (see our ratings guide for more information).

And finally, let's look at how this data corresponds to S&P500 performance.

This final chart shows two important ideas:

Visualizing Valuation Opportunities

The main line illustrates the S&P 500 since 1950, with colors indicating the standard deviation bands from our model. For instance, when the S&P 500 fell more than 1 standard deviation below its P/E average—like in 1950 and again from the mid-70s to the mid-80s—the chart is shaded green, highlighting undervaluation and presenting a buying opportunity.

Increasing Earnings

The dotted line in the chart above represents the price level of the S&P 500 if it were consistently valued at the modern-era P/E (CAPE) average of 19.8. In other words, the dotted line is essentially 20 times the CAPE ratio. This line is rising at an unprecedented rate, as corporate earnings have surged over the past 30 years, largely fueled by the tech boom.

Criticisms of The Model

No single model fully captures market valuation. Below are some key points to consider when evaluating the PE10 model:

Market Composition Changes

The primary criticism of using historical PE ratios as a valuation metric is the belief that PE ratios should naturally rise over time. A clear example of this shift is the changing market dynamics, where an increasing emphasis on high-growth tech stocks has likely led to higher average CAPE ratios in recent years. Additionally, external factors such as Federal Reserve interest rate policies, which encourage low rates and high growth, have likely played a role in this trend. If the economy and industries do not return to the conditions of the 1960s, there’s little reason to expect market P/E ratios to revert to those historical levels.

It's clear that the CAPE ratio has risen over time, especially since around 2000, as tech and growth stocks have taken a larger share of the S&P 500. We recognize that comparing today's market to that of the 1800s isn't practical, which is why we avoid using data from before 1950 in this model. While the average CAPE ratio has steadily increased since 1950, it’s still worth questioning what the 'natural' rate of that increase should be.

Interest Rates

Similar to the Buffett Indicator, the CAPE ratio doesn't account for the current interest rate environment. Lower interest rates typically justify higher valuations because they reduce the cost of capital and increase the present value of future cash flows. Fortunately, we examine the relationship between interest rates and stock prices in greater detail in our Interest Rate Model.

Delayed Reflection of Current Profitability Trends

The ten-year earnings average used in the CAPE ratio may not quickly reflect the latest profitability trends, especially in fast-evolving industries or during periods of economic instability. This lag can make the CAPE ratio less useful as a real-time stock market valuation tool, particularly in sectors that are greatly impacted by technological advancements and innovation.

For example, if AI leads to a surge in productivity in the coming years, we could see a significant boost in short- and mid-term profits for companies. However, this increase may not be fully captured in the CAPE ratio for a decade. As a result, the CAPE ratio could suggest that the market is overvalued, even when it might not be. Investors seeking timely insights should consider other metrics and indicators that more quickly respond to shifts in profitability.