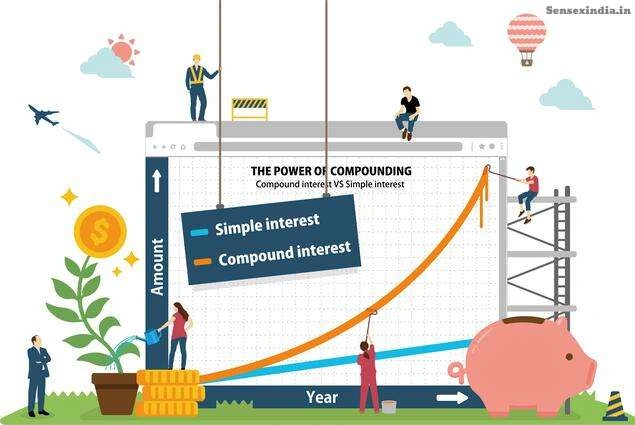

Compounding refers to the process where the earnings generated from an asset, whether through capital gains or interest, are reinvested to earn additional returns over time. This growth occurs through exponential calculations, as the investment generates earnings not only on the initial principal but also on the accumulated earnings from prior periods.

Unlike linear growth, where interest is applied solely on the principal, compounding amplifies growth by considering both the principal and its accumulated interest over time.

Key Takeaways

- Compounding involves applying interest to both the principal and previously accumulated interest.

- Known as the “miracle of compounding,” this process magnifies returns over time.

- Financial institutions typically use compounding periods such as annually, monthly, or daily.

- Compounding can make savings grow quickly or increase debt even when payments are made.

- Savings accounts and certain investments with dividends can benefit from compounding.

Understanding Compounding

Compounding refers to the increase in the value of an asset, where the interest earned is added to both the principal and previous interest. This concept is tied to the time value of money (TVM) and is closely linked to compound interest.

In finance, compounding is a powerful tool, driving many investment strategies. For instance, dividend reinvestment plans (DRIPs) enable investors to reinvest dividends to purchase more shares, leading to compounded returns over time. This reinvestment strategy generates additional income from dividend payouts, assuming consistent dividend rates.

Some investors refer to this strategy as “double compounding,” where the dividends themselves are reinvested into stocks that increase their per-share payouts.

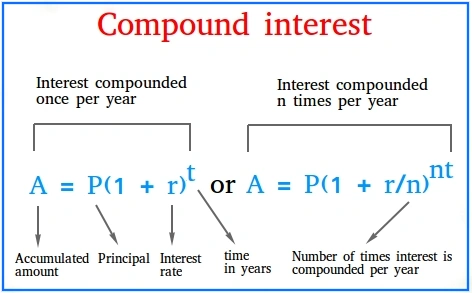

Formula for Compound Interest

The formula for determining the future value (FV) of an asset relies on compound interest, considering the present value, the annual interest rate, the compounding frequency, and the number of years. The general formula for compound interest is:

This formula assumes that the principal balance remains unchanged, except for the interest applied.

Increased Compounding Periods

As the frequency of compounding increases, so does the effect on the future value of the investment. For example, consider a one-year period—more frequent compounding leads to a higher future value. Therefore, quarterly compounding yields better returns than semi-annual compounding, and monthly compounding is better than quarterly.

Let’s take an investment of $1 million earning 20% per year. Here’s the future value based on different compounding periods:

- Annual compounding (n = 1): FV = $1,000,000 × [1 + (20%/1)] (1 x 1) = $1,200,000

- Semi-annual compounding (n = 2): FV = $1,000,000 × [1 + (20%/2)] (2 x 1) = $1,210,000

- Quarterly compounding (n = 4): FV = $1,000,000 × [1 + (20%/4)] (4 x 1) = $1,215,506

- Monthly compounding (n = 12): FV = $1,000,000 × [1 + (20%/12)] (12 x 1) = $1,219,391

- Weekly compounding (n = 52): FV = $1,000,000 × [1 + (20%/52)] (52 x 1) = $1,220,934

- Daily compounding (n = 365): FV = $1,000,000 × [1 + (20%/365)] (365 x 1) = $1,221,336

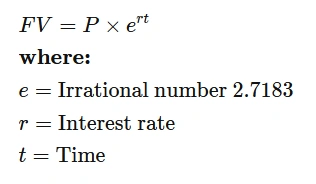

As shown, the increase in future value diminishes with more frequent compounding periods, reflecting a limit known as continuous compounding, which can be calculated with:

With continuous compounding, the future value is: FV = $1,000,000 × 2.7183 (0.2 x 1) = $1,221,403.

FAST FACT

Compounding is often compared to the "snowball effect," where a small initial change builds progressively over time.

Compounding on Investments and Debt

While compounding accelerates the growth of an asset, it can also increase the amount owed on a debt, as interest accumulates on both the principal and the unpaid interest. Even if you are making payments, the compounding effect may result in a larger debt in future periods.

This effect is especially prominent in credit card debt, where high interest rates and compounding interest charges can substantially increase the amount owed over time. Compounding, therefore, can have both positive and negative consequences depending on the situation.